Visual Culture: Drawing Dudus with Hubert Neal, Jr. | Large Up

August 31, 2010

Words by Erin MacLeod

Photos by Martei Korley

Original Art by Hubert Neal, Jr.

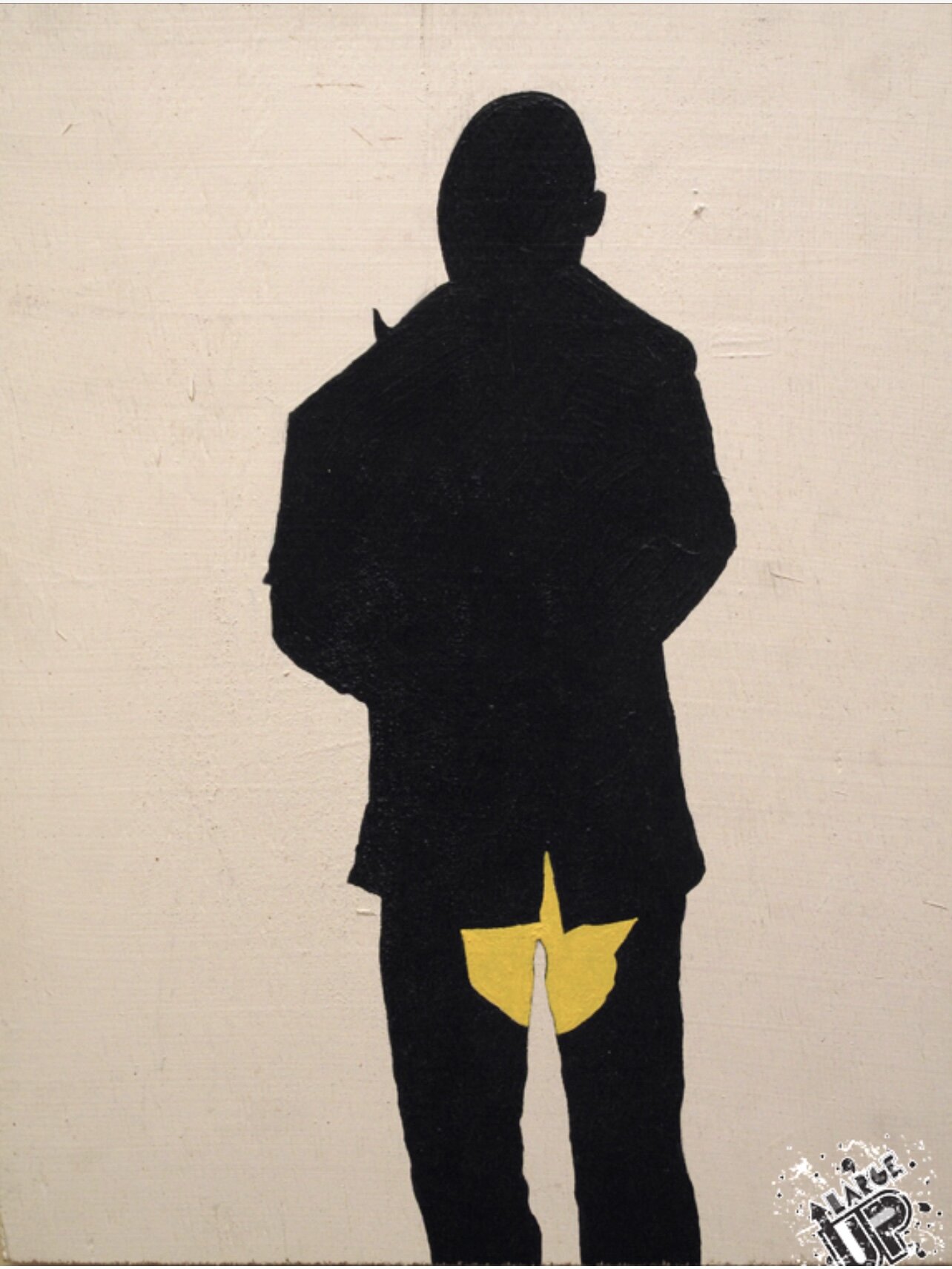

The Hunt for Dudus

When Belizean artist Hubert Neal, Jr. arrived in Kingston, Jamaica on May 20, 2010 to start a residency at Melinda Brown’s Roktowa studio, he had plans to paint Jamaica. Three days later, the military and police invaded Tivoli Gardens in hot pursuit of Christopher “Dudus” Coke, a man who had been, for months, wanted for extradition by the United States of America. The hunt for Coke and its accompanying media coverage was impossible to ignore, and Neal began to paint. The results of this process was a series of twenty-six works titled The Dudus Chronicles, on display now at the Grosvenor Galleries in Kingston. It’s colorful and varied–but also quite disturbing, never shying away from depicting the violence that accompanied the search for Dudus. Largeup caught up with Neal during his last few days in Jamaica to talk about his process, his work, and his position as an outsider looking in.

Largeup: As a Belizean, can you tell me how you ended up focusing on doing something with Jamaica as subject?

Hubert Neal: Anybody from the islands or places that are essentially Caribbean nations will talk about Jamaica as a beacon—it’s the prototype. For those of us who speak English, there is a common accent. But reggae music is also such a part of all our lives. In Trinidad, their indigenous music is soca. Ours in Belize is punta, but during any party, eventually you have to throw on the reggae. So this is how we grow up. So it’s a natural progression. Jamaica’s been a standard-bearer and we just have an affinity for it. I’m just surprised that I didn’t come sooner!

I came to do a residency. I thought I might do something on dancehall or the Blue Mountains or all these other things that we know about Jamaica or hear about Jamaica—I would have focused on those things. But since this Dudus situation came up, that’s what got my attention.

Come One, Come All

Q: I think it’s important to note that the place where you did the residency, Roktowa, is in the downtown area. You arrive thinking you are going to do a project on the Blue Mountains and…

A: …there’s a state of emergency. Trying to get to the studio, we were told we had to take certain streets, you can’t take this street—soldiers were asking, “What do you need to be down here for?” We’d say, We have to get to our studio–but there’d be barbed wire and barricades on every street. To let us through they’d look at us, ask questions, pat us down, and I was thinking, Ok, I just came for a residency. I didn’t come for this. Eventually I just said this is a little too close for comfort and I started taking pictures, because I also do photography. These are all different tools: the paintbrush, pencils, camera. I realized that this was a very rich subject, and I started to ask more about what was going on, who is this guy that they’re after? But when you have armed guards and soldiers and soldiers and police with machine guns, it’s like, Ok, where is all this going? And that’s when I realized that I had found my subject.

The Extradition of Jim Brown

Q: You’ve said you really only planned on doing one.

A: Yes. The largest one, called “The Hunt for Dudus.” It’s in panels—little pieces of the saga up to that point. I thought, Ok, I will do a synopsis and then I will be done. I had no intention of doing a series, though I am the type of person that thinks in terms of themes. Not being from here, you can’t force it. But as days went by, and days turned into weeks, and weeks turned into months, you realize that there are all these little stories going on that add to this. There are parts all over the place.

Q: There have been a lot of discussions about the Jamaican media coverage of the state of emergency. On the Ground News Reports being established on Facebook and Twitter suggested that there was a need to report and reflect more immediately and directly what was actually happening. What was your perspective?

A: I’ve always been a kind of documentarian; I’ve always been concerned with social issues, context and history—I also have a background as a photojournalist too. I can write and draw—I use different tools to tell a story. What I’m most concerned about is being honest and being authentic and not passing judgment—which I’m not doing. I am responding, and I’m absorbing and I’m inhaling and I’m spitting back out what I’ve digested. Which is all I can do. The dominant thing is that, while I’m doing it, I’m not thinking, “Oh gosh, is this dangerous? Am I going to get arrested for doing this stuff?” I thought about that after.

Q: As someone who is coming from the outside, how do you respond to a person who might think that this type of art should have been done by someone who understood the context, someone who had been in Jamaica for a longer period?

Bloody Tivoli

A: I have responded to that type of comment. But first, let me say that everyone that has come to me thus far has been positive, which is actually quite surprising. I was expecting random emails, anonymous comments, but there has been none of that. One woman at my show asked if I was taking advantage and we had a long conversation and she ended up shaking my hand, but not before it got really contentious! She did say, “But you’re the only one that’s doing this.” And I said, That’s a shame. It’s a shame that I’m a foreigner coming to Jamaica telling a Jamaican story. I understand that there are a lot of people who couldn’t pay attention to this, people who couldn’t go to work, who couldn’t go to school, people that are injured and people that are dead. But–I said to her–you do have artists here who are taking photographs, writing, painting, who are making a living from their art and have the freedom and aren’t doing this. Now I’m not passing judgment, it could be because they are from here—it hits them in a different way. I have a certain amount of detachment. It’s hard. But there are also some reasons that have nothing to do with this. Reasons that aren’t that deep—I just work fast! I process things fast. So it could be as simple as that. But when she came at me like that, I said that it really is a shame that I am the first. I should not have been the first; I wasn’t trying to be.

Q: Speaking to you it seems like you certainly hope you aren’t the last.

A: Oh gosh. I hope not! In fact, I hope that people say, Look at this guy—how is he able to get all this done and out? Maybe, though, it’s like a 9/11 thing. When do you respond to it; is it too soon? I’m sure these are a lot of the types of questions that are going on. I just don’t think like that and I hope that if anyone has any issues they will approach me and see how I’m doing. But I really don’t think about being afraid or, Should I or should I not? I’m a slave to my art. That’s what I do. I paint, I create—sometimes it is more painful for me to not create.

Q: The works range from an almost hyper-realism in “Solitary” to figurative images portrayed in a more abstract fashion–as in the May Pen paintings–through to almost Egyptian, hieroglyphic images and then cartoonish depictions as in the “Driving Ms. Dudus” painting.

Driving Ms Dudus

A: They are different tools. You have people, generally not artists, but people who want to put you in a bin. They want to know how to classify you. We don’t care about such things. We just do what we do. I’m just blessed with a wide range. I believe that to effectively communicate with people you have to do so in different ways. Some of that cartoon-y graphic stuff is a response to the way people communicate right now; the way we have iPods and iPhones and commercials that last ten seconds. These are all the ways that people respond. It’s not enough to do something realistically. Just because you might have the talent or the skill doesn’t make it art.

Q: What’s interesting is that it opens things up. The different pieces, when you see them all together, open up different avenues of interpretation in reaction to the events of May in Jamaica. It allows for different perspectives to coexist, and that ends up being represented by these different images from the realistic to the unrealistic: from the seriousness of the really and truly disturbing May Pen photographs to the ridiculousness of the image of Dudus in a wig.

A: Thank you. Because life is not just one way. Sometimes it is serious, sometimes it is disturbing, sometimes it is absurd, sometimes it is funny…I am responding to each thing. You are not telling me that him being caught with a wig on is not making you laugh. The approach has to be such that it will address that, to be honest.

May Pen Still Life #3

Q: Given the obvious trauma that this event inflicted on Jamaica in general, Kingston in particular and especially Tivoli, is there any kind of usefulness that this art could provide in this context?

A: Actually, there is a young lady I met at the gallery who would like to bring young people who were impacted by the event, arrested during the incursion or who are budding artists from the area, and she wants to bring them in to see the work as part of art therapy…and to inspire them, and have them think in a more broad sense. I couldn’t think of a better way to have the work interact with people.

Wet